Descending the steps into the London Underground, I heard someone - a busker most likely - playing a piece of classical music. All of a sudden, I could picture dancers - beautiful, ethereal dancers.

The image faded as I made my way to the platform. However, I also noticed - and corrected - my posture. The reason for this (for me, rather unusual) behaviour? I had just watched Cunningham - Alla Kovgan’s documentary about the incredible career of legendary dancer, teacher and choreographer, Merce Cunningham.

My Underground epiphany aside, I confess to knowing next to nothing about dance. As a result, I find modern dance both deeply impressive and also utterly bewildering. Fortunately, Cunningham does not demand any prior dance knowledge or expertise.

Indeed, in the film, Merce Cunningham refuses to be limited by the act of definition: “I don’t describe it, I do it”. However, he does reveal that he was inspired by ballet techniques for leg work and modern dance for the torso. The result is a series of timeless, avant garde dance creations.

Cunningham’s story is told via stylistically arranged 16mm and 35mm archive footage, photographs and audio clips from Merce Cunningham’s 70 year career. There are few of the tropes traditionally found in documentary biopics (no talking heads, no one there to tell us what to think).

“I conceived Cunningham as a 90-minute artwork in itself, which tells Merce’s story through his dances,” explains Kovgan. “The film is a hybrid, rooted in both imaginary worlds and moving life experiences. It aspires to find a delicate balance between facts and metaphors, exposition and poetry.”

Far from a series of random moves, Kovgan’s documentary shows us how the steps of each dance piece are carefully choreographed. The film, the result of seven years of research, also reveals how open Cunningham was to collaboration both from his dancers and other artists.

Kovgan’s documentary features intimate and often humorous recollections from Cunningham’s partner, composer John Cage, and fascinating insights from artistic collaborator, Robert Rauschenberg. We also hear from Cunningham himself and witness both his creative passion and his self effacing charm.

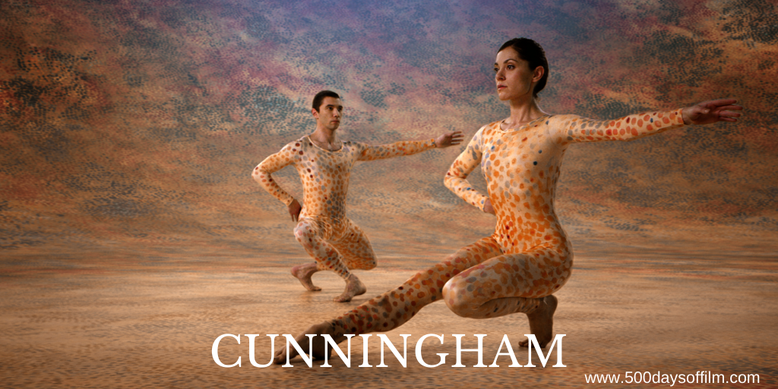

Interspersed are beautifully choreographed dance sequences - excerpts from 14 of Cunningham’s dances. Kovgan has translated these dances into something breathtakingly cinematic. Set in a variety of stunning locations (rooftops, forests, gorgeous indoor spaces), immersive camerawork takes us inside the dance.

Watching these remarkable, beautiful scenes, I began to question my bewilderment concerning modern dance. Perhaps, I thought, it stems from a need to make sense out of something determined to break free of order and conformity.

Whatever the reason, watching Cunningham encouraged me to relax and simply experience the dance. I particularly enjoyed Crises, Summerspace and the tension-fuelled Winterbranch. It is nothing short of mesmerising.

I found myself transfixed by the feet of the dancers - both watching them and listening to the sound they made as they rose and fell, rose and fell. It reminded me of watching an orchestra playing a complicated piece of music - enchanting but also full of physicality and tension, one wrong move and the magic is lost.

Cunningham’s magic is safe in Kovgan’s meticulous hands. “We combed through each take, eliminating those with any obvious mistakes and only choosing the best in regards to performance and camera work,” Jennifer Goggans, the film’s director of choreography recalls. “This part of the process was tricky in that we both were fighting for perfection.”

I watched Cunningham in 3D. I am no great fan of this technology but here it made sense. “3D offers interesting opportunities as it articulates the relationship between the dancers in and to the space, awaking a kinesthetic response among the viewers,” says Kovgan. “Merce and 3D represent an ideal fit, not only because of his use of space but also because of his interest in every technological advancement of his time.”

Meanwhile, the film’s archive footage remains in 2D. Kovgan explains that she worked with the footage “as a sculptor would, collaging them in 3D cinema space. The aspiration has been to develop a unique language, integrating all the elements of the film in a subtle, distinct and poetic way – in Merce’s spirit.”

However, despite the many advantages of 3D technology (particularly in the field of dance), 3D is not absolutely necessary to enjoy this documentary. I believe that the film will look just as beautiful in 2D (Cunningham is now available to rent online).

Immersion is what is more important. You need to immerse yourself in Kovgan’s film in order to appreciate the story that she is telling. Only then will its power take hold. Only then might you be able to imagine a world of dance while standing on a train platform.