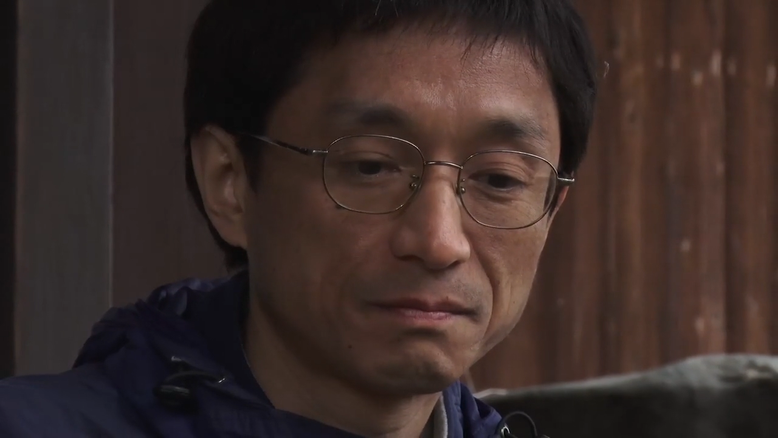

In Me And The Cult Leader, director Atsushi Sakahara, a victim of the 1995 sarin gas attack in Tokyo's subway system, goes on a journey with Hiroshi Araki, an executive of Aleph (formerly Aum Shinrikyo) - the attack's perpetrators.

The film is a powerful look at Aum’s human face. It explores the consequences of joining a cult and the lasting impact of this horrific and extremely traumatic event.

I was lucky enough to talk to Atsushi Sakahara about his experience of making his debut documentary feature.

How did you come up with the idea for Me and The Cult Leader?

I happen to have had a unique experience - both in surviving the subway attack and also marrying a woman who used to be a part of the cult. I was looking for a project and decided to do something autobiographical.

I would always ask myself - what do I know about Aum? I knew that if I wanted to describe my experience I would also need to understand Aum. This was the question that I started with and that led me to the idea of a documentary film.

How did Aum react to your documentary film proposal?

I had to convince the executive committee. I went to see them and explained who I am and what film I was interested in making. I had to convince them that - while I was not going to be easy on them - I am a person who will listen. I am not prejudiced.

I talked - a lot.

I saturated Hiroshi Araki with information about me and my life. Soon he began to open up and talk to me about his experience. However, I had to ask him not to tell me his story until we were filming.

The final Aum trial took place during the pre-production of your film. How did this influence the documentary?

During pre-production, I met a newspaper journalist. He suggested that I attend the last Aum case trial. It was a jury trial and I sat in the court.

It took quite an effort for me to be there. I contacted the public prosecutor to ask if I could be in court. She said no and I felt really angry. I told the public prosecutor that I was going to ask the court judge to be allowed in court. She told me that I couldn’t meet the court judge.

I argued that if I was not allowed to attend the court, I would stand in front of the courthouse with a placard that said “Open Court. Open Trial”. As this is a socially important trial, it should be open for all society. In the end, I managed to convince the public prosecutor to allow me to sit in court.

That trial was a miracle for me. Before then, I had tried not to face Aum issues and I had avoided Aum news. At the trial I learned so much because the public prosecutor and Aum’s lawyers had to explain everything.

This meant that when it came to making the documentary, I was really well informed and knew the incidents in detail. That experience helped me to think clearly about what I wanted to do in the film.

What did you hope to achieve by making this film?

To be honest, I wanted to convince Araki to leave. That would have been the perfect end to the story. This was, perhaps, rather naive.

Why do you think that Hiroshi Araki agreed to take part in your film?

I appreciate the fact that Araki let me shoot this documentary. It was very courageous of him. I took a risk but he also took a risk.

There are many reasons why he agreed to take part. He wanted to pay one victim back - a gesture on behalf of Aum. Maybe he was hoping that the Japanese government or society would then tolerate the cult.

Also, Araki thought it was fate because we have so many similarities. This, for me, was just a coincidence - I am very scientific. However, Araki felt it was fate and wanted to explore the connection to see what would happen.

It is amazing to see how many similarities there are between you and Araki…

Watching the film, you might think that I planned it all this way but that was not the case. Making a documentary is like cooking at midnight… you can only work with what you have in the fridge.

Why did you decide to incorporate a journey into the story?

I always wanted to structure the film around a journey. I had many ideas. One was for us to drive across America. However, Araki cannot go to the US because he is viewed as a terrorist. I had lots of other ideas… including going up a mountain. However, I realised my film crew would not love this idea!

Was the journey challenging to organise?

This journey was like my pilgrimage. I pre-planned everything and the pre-production process took over a year.

I had to think carefully about the order of our journey. I always arranged for us to visit my places first. I went to my hometown first. As I introduced him to my life, he began to introduce himself back.

Was it hard to know how far to push Araki on the more difficult aspects of his life?

Yes. I would experiment and see how he responded. One day he said that if I kept asking him questions in a certain way he would go home. I had to find his limits. I would get closer to the limit and then go back, get closer and then go back.

Was it hard to encourage Araki to speak freely?

Araki is very smart, very sharp. He would always try to rephrase the same thing that he was asked. Off camera, he revealed that this is his debate technique.

The scene in the documentary with your parents is extremely moving. Did you always intend to involve them in the film?

From the very beginning, I knew that I wanted to include my parents.

I had an option to introduce Araki without letting him know that they were my parents. However, I decided not to do that - even though I was tempted, it did not feel right.

During the shooting trip, I asked him if he would like to meet my parents and he thought about it and then agreed.

It was not easy to convince my parents. They did not know what they should say to Araki. I told them to say whatever they felt like in that moment.

We only had one hour to shoot that scene in the tea house. I had the option of leaving without having Araki apologise to my parents. I knew that for Aum people it is very hard to apologise. However, if I did that, it would make him and his family look very bad to the audience.

The film explores a very traumatic event in your life. Was it hard to be the director, producer and subject?

Yes. After I pushed Araki, I would try to do or say something funny. However, subconsciously I was feeling a lot of stress.

Many times during the shoot I felt really sleepy and sometimes I closed my eyes and almost fell asleep. This is a result of my PTSD. I didn’t realise this until very recently - it is a psychological self defence mechanism.

This is your first documentary film. How did you find the experience?

As this is my first documentary, I didn’t know what directors usually have to worry about. I was the film director and producer. So while we were shooting, 70 per cent of my brain was thinking: where should I feed my crew?

We had a van but we mostly travelled via public transport. So I had to buy tickets. I had to do everything and that was a challenge. I also did the crowdfunding and lots of media outlets were contacting me on the phone - it was crazy. I cannot do that again!

The film is such a miracle - no matter how you make a film, it is a miracle.

Can you tell me anything about any future projects you are planning?

I have some projects in mind and I am planning to write my autobiography in English and make an autobiographical film.

I would make a sequel to Me and the Cult Leader - but only if or when Araki has left Aum and found a new way of living.

I would like to thank Atsushi Sakahara for talking to me about his film and for being so generous with his time.