In 2014, a box was found in a storage unit in Los Angeles. The box contained hundreds of letters dating back to the 1950s - all of them were addressed to a former radio broadcaster called Reno Martin.

The content of these letters proved to be a rich and rare archive, full of fabulous insights into a forgotten era - the underground drag scene in 1950s New York.

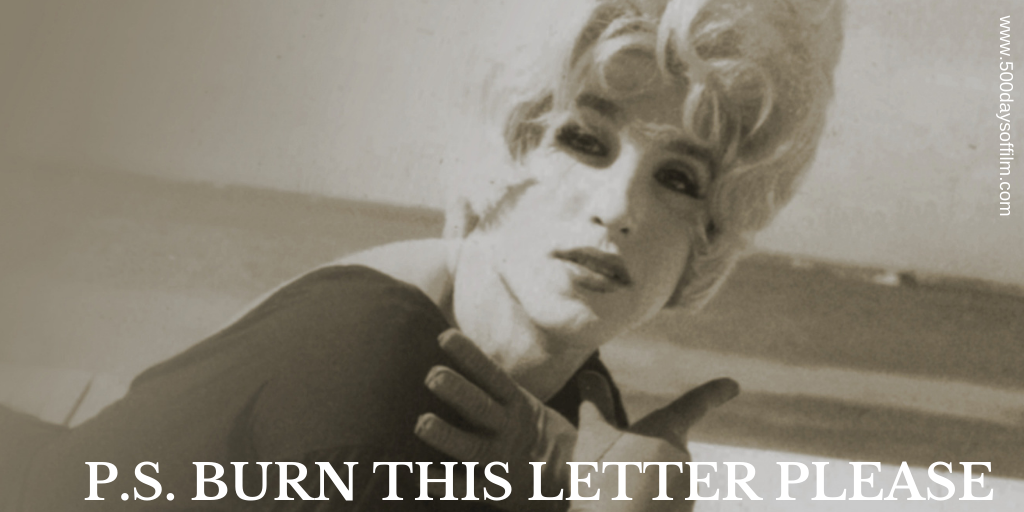

Featuring fascinating interviews, animated scenes and painstakingly researched archival material (the project took five years to complete), P.S. Burn This Letter Please brings this treasure trove of documents to life.

Reconstructing the experiences of the letter writers themselves - now all in their eighties and nineties - Michael Seligman and Jennifer Tiexiera’s wonderful and deeply moving documentary reveals powerful details about an invisible history.

It is such a pleasure (and a privilege) to meet the letter writers. They all have entertaining and empowering stories to tell. Decades before Stonewall, many were attracted to New York because they could find work as female impersonators in a small number of Lower East Side clubs.

Determined to live the lives they wanted to lead, they were unstoppable, fearless and beautiful. Their costumes and wigs were fabulous (not all were acquired via lawful means… watch out for some Oceans 11 style antics) and the film’s use of archive footage and photos of parties, balls and club nights is a joy.

It is also wonderful to learn about the development of such an exciting, diverse and supportive community. The documentary explores, for example, how drag balls were integrated at a time when segregation was the norm.

However, these were lives lived under the constant threat of violence. New York drag queens and female impersonators were also at risk of arrest - the police would routinely raid drag parties. In short, society either punished their community or used it for entertainment.

Seligman and Tiexiera’s documentary explores the impact of how in those days, if they were outed, LGBT people were often viewed as being mentally ill. Many were referred to psychiatric wards for “treatment”. No surprise, then, that some of the letter writers asked “Dear Reno” to destroy their correspondence after reading.

This led to a tragic lack of records and documentation. The people were invisible and so was their history. This was, of course, compounded in the late 80s, early 90s, when the world of drag queens and female mimics began to experience devastating loss as a result of the spread of AIDS.

As a result, this powerful collection of stories from a generation of incredible survivors feels so important. Thank goodness Reno Martin did not burn these letters.