Marion Stokes recorded television twenty-four hours a day on multiple channels for thirty years. Yes, you read that correctly - twenty four hours a day, for thirty years. Matt Wolf’s superb documentary, Recorder: The Marion Stokes Project, explores Marion's remarkable life and incredible legacy.

Marion’s secret archive began in 1979, with taped televised coverage of the Iran hostage crisis at the dawn of the twenty-four hour news cycle. The recordings finally ended when Marion died, aged 83, on 14th December, 2012. Heartbreakingly, she passed away as devastating footage of the massacre at Sandy Hook played on the televisions surrounding her.

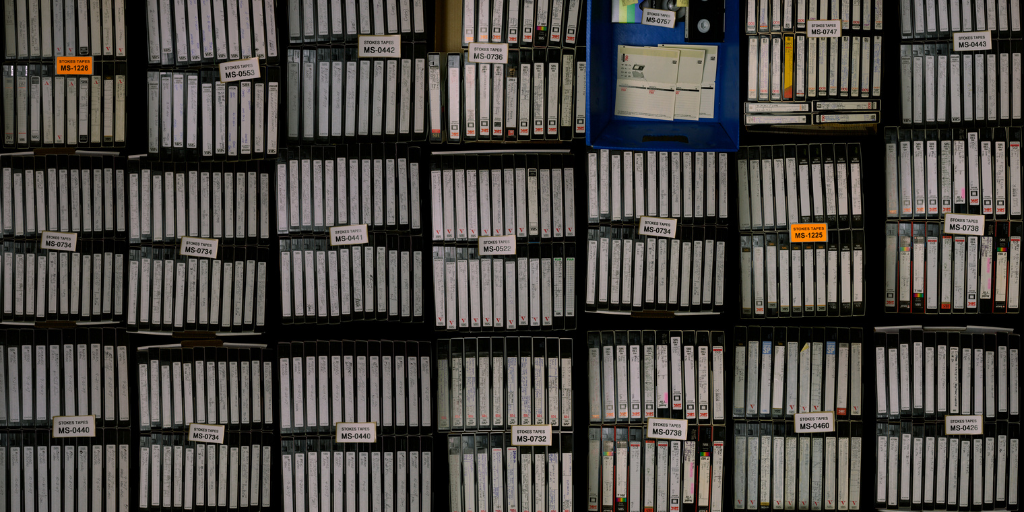

In all, Marion’s collection featured 70,000 VHS tapes. On important news days, eight VHS machines would be recording at once. On "normal days", only three-five recorders would be in constant use. As a result, Marion captured wars, revolutions, lies, triumphs, tragedies, catastrophes, documentaries, sitcoms, talk shows and commercials.

When considering her remarkable project, the first question that comes to mind is… why? “People always ask why. Why did she do it?” Marion’s son, Micheal Metelits, says in the documentary. “To understand that, you really need to know who my mother was and the life she lived.”

As Recorder reveals, Marion lived an extraordinary life. Born in 1929 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania she was well versed in politics and was, at one point, considered to be a potential leader of the Communist party. Later on, Marion produced and appeared on Input, the political and current affairs discussion programme.

Marion was a huge fan of technology and an early investor in Apple, which increased both her personal and her family's wealth (she lived, we are told, in an apartment in the richest part of Philadelphia). Marion collected what Micheal describes as “enormous amounts of Apple technology” and greatly admired Steve Jobs.

However, above all else, Marion was an activist, motivated by her fear that America would replicate Nazi Germany and her passionate belief in human freedom. Micheal believes that his mother’s archive was a form of her activistism - a way to seek the truth and check the facts.

Marion's project began during the Iran hostage crisis when she became suspicious of the televised reporting of the situation. She was worried that important information was being lost (or even suppressed) as the story evolved and that public opinion was being moulded (in this case, towards an anti-Iranian narrative).

Marion’s concerns about the impact of the twenty-four hour news cycle grew. She was deeply uncomfortable with television's power to inform and misinform. As a result, Marion believed her recordings were of supreme importance - holding the media and society to account.

However, Marion’s project came at a price. Recorder examines the toll her obsession took on her family. Long before she began recording, Marion was difficult and challenging. She appeared to value her archive above all else. Micheal remembers his mother being “cruel” and having unrealistically high standards. His intimate recollections in Recorder reveal a complicated and often troubled relationship.

Meanwhile, Marion’s first husband, Melvin Metelits, describes her as being “loyal to her own preferences and tendencies and beliefs”. When he did not live up to her expectations, Melvin recalls being subject to “withering criticism”. The marriage did not last.

Marion went on to find lasting love and friendship with a man called John Stokes. John’s daughters, Anne and Mizzy, talk frankly in Recorder about Marion and John’s marriage. Sharing similar ideals, their relationship was intense - they lived largely in isolation and would rarely be apart.

Anne, Mizzy and Micheal could easily be forgiven for harbouring resentment at being cut off from Marion and John - particularly as the couple went on to form a quasi-family with Marion's chauffeur, Richard Stevens, her nurse, Anna Lofton, and her assistant, Frank Hellman.

However, while Marion's relationships were undeniably complicated, the documentary contains no sense of ill will. The memories shared from all those involved in Marion's life are deeply moving, full of love and respect.

As Recorder tells Marion’s intriguing story, so we see clips from her collection. The management and editing of this footage is endlessly impressive. All too easily, the documentary could have become suffocated by the unprecedented size of this archive. Thankfully, Wolf proves (once again) to be a masterful curator of archive footage.

Some of the recordings are familiar - the operation to save baby Jessica from a well in Texas, preparations for the millennium, footage of wars, of tragedies and of key moments in political history. However, just as powerful are the snippets from local news - 100 year old twins celebrate their birthday, a man is buried in his car.

The clips possess a powerful cumulative impact (no more so than in footage following the 9/11 terrorist attacks). Here is a record of humanity that is, perhaps, more truthful and more insightful than you will find in many history books. In addition, long before “fake news”, Marion's archive shows us how television filters information, how it seeks to shape public opinion.

The final act of Recorder explores what happened to Marion’s tapes after she died. Shots of the VHS tapes - the physical reality of thirty years of television recordings - are stunning to behold.

While the full impact of her project may yet be known, Recorder leaves us in no doubt of Marion Stokes' contribution to human history. Hers is a legacy that should be both acknowledged and celebrated.