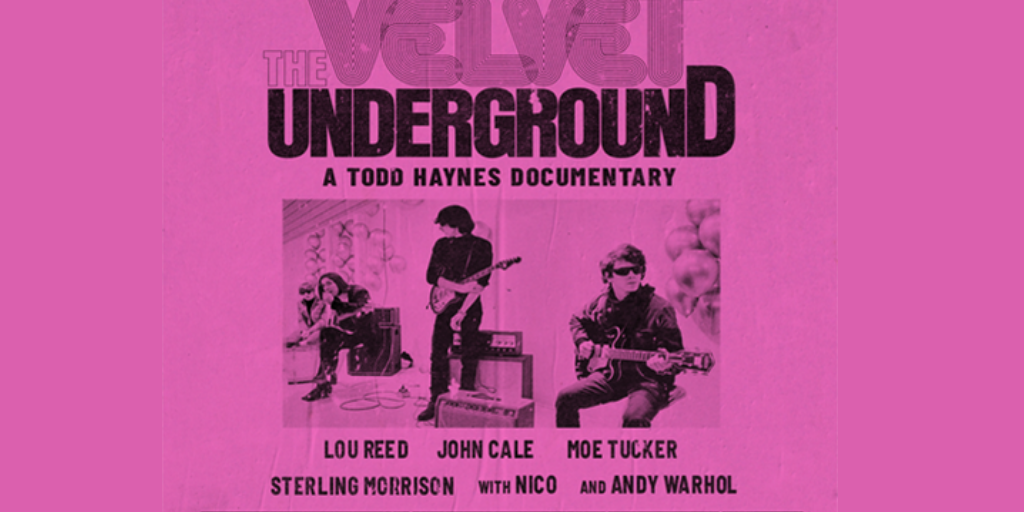

When asked about the experience of making his first documentary, director Todd Haynes appeared reluctant to categorise his work as nonfiction. This film, he suggested at the 2021 BFI London Film Festival, was less to do with truth and more a poetic exploration of influential and iconic band, The Velvet Underground.

Initially, this felt (to me, at least) like a snub to nonfiction cinema. Why so hesitant to call this a documentary, Mr Haynes? However, as I watched The Velvet Underground, I began to understand the director’s point. The Velvets were, of course, brilliantly experimental and resisted binary definitions. Haynes tries to mirror this in his film - resisting many of the tropes familiar in music documentaries as he charts the band’s exciting and chaotic journey.

However, The Velvet Underground is, for all these elements, still very much a documentary.

It is also a much anticipated film. Fans of the Velvets have long awaited a documentary about their beloved band. They will not be disappointed. This is a passionate, intelligent and insightful examination of a fascinating group of musicians. Haynes’s film delves deep into the band’s incredible, sometimes confrontational talent, examines their relationship with Andy Warhol (utilising Warhol’s footage of the band to great effect) and documents the tensions that inspired stunning moments of both creativity and controversy.

While the documentary is not definitive (despite its running time of over two hours), The Velvet Underground is an impressive and, at times, poignant, portrait.

Haynes conveys The Velvet Underground’s creative energy via a trove of archive materials - often presented in split screen. Editors, Affonso Gonçalves and Adam Kurnitz, do a tremendous job of pulling all the footage and photographs together. The use of archive is often an assault on the senses - which, you sense, is exactly the point.

As a result, it is something of a relief when the film cuts to a “talking head”. The documentary features a number of new interviews with band members John Cale and Maureen "Moe" Tucker and people who witnessed the band’s magic - including actor Mary Woronov and author and film critic Amy Taubin.

It is in these interviews that the film comes alive (particularly when Tucker and Woronov talk about their disdain for California's hippy community) and I was left wanting even more. The trouble with loading The Velvet Underground with so much archive (understandable given the lack of footage of the band) is that it had, for me, a stifling and sometimes frustrating effect.

Another frustration is the lack of attention paid to Moe Tucker. It is, of course, wonderful to hear about John Cale and Lou Reed. Cale’s recollections of his time with the Velvets are a joy. I would, however, have loved to hear more about Tucker’s experience - and particularly about her brilliant, unconventional drumming style.

This was one of a number of omissions that I noted in Haynes’s film. However, while The Velvet Underground may not be a definitive account, it is still incredibly impressive - reminding us of the mysterious alchemy that made the Velvets such an iconic part of music history.