“For more than half an hour 38 respectable, law‐abiding citizens in Queens watched a killer stalk and stab a woman in three separate attacks in Kew Gardens.

Twice the sound of their voices and the sudden glow of their bedroom Iights interrupted him and frightened him off. Each time he returned, sought her out and stabbed her again. Not one person telephoned the police during the assault; one witness called after the woman was dead.”

Extract from Martin Gansberg’s March 1964 article, 37 Who Saw Murder Didn't Call the Police; Apathy at Stabbing of Queens Woman Shocks Inspector,

published in The New York Times

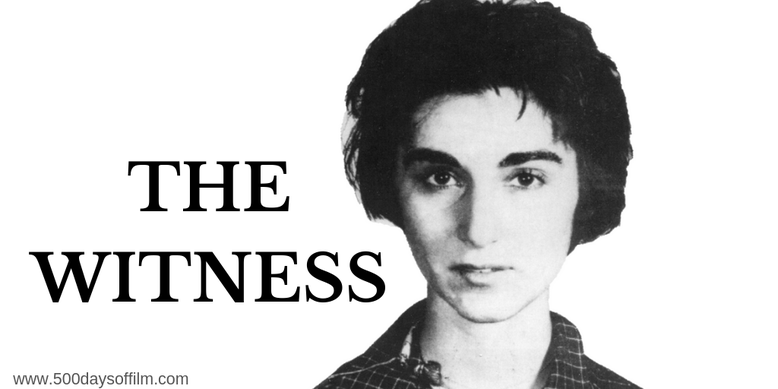

For 40 years, this was the story of the death of 28 year-old Catherine “Kitty” Genovese. 38 people witnessed a brutally violent, ultimately fatal attack and did nothing. With one phone call from the safety of their own homes, 38 people had the chance to save Kitty’s life.

However, they didn’t want to get involved.

Unsurprisingly, following the publication of Martin Gansberg’s shocking article, the murder of Kitty Genovese attracted widespread attention.

The media questioned whether witnesses should be held accountable if they failed to act, psychologists sought to understand bystander apathy (what would later become known as “Kitty Genovese syndrome”) and politicians used Kitty’s death as an example of moral decline and an increasingly uncaring America.

Kitty became a metaphor, her name a siren call for change. And change did come. Following her death, many safety initiatives were launched - including America’s 911 emergency system.

Meanwhile, for 40 years, her murder was used in both fiction and non-fiction stories. Over that time, the real Kitty Genovese became lost among the theories, books, headlines, television episodes and films.

Screenwriter, James Solomon, was asked to write a script about the murder for HBO. “The story stayed with me, undeniable as it was for what it said about human nature,” Solomon recalls. “I saw the movie as a morality play and wanted to explore what happened in those apartments.”

Solomon’s research led him to Kitty’s brother, William (Bill) Genovese. Bill was 16 when Kitty died. Her murder devastated him and his entire family - particularly following the details revealed in The New York Times article.

The lasting impact of the narrative behind Kitty Genovese’s murder cannot be exagerated. Kitty was a beloved daughter, sister, friend and partner... and she could have been saved.

However, it was all based on a terrible lie.

In February 2004, 40 years after Kitty’s murder, journalist Jim Rasenberger published an article in The New York Times questioning the accuracy of Gansberg’s story. While it fell short of accepting responsibility for the mis-reporting of the case, the story stunned Bill Genovese.

“Bill, who had been close to his big sister, became determined to find out for himself

what actually took place that night,” Solomon explains. “I proposed the idea of documenting his investigation. We were united in the belief that there had been enough fictionalising of the Genovese story and that a documentary would bring us closer to the truth.”

Neither Bill Genovese nor James Solomon could have predicted the journey that would follow. The Witness - Solomon’s directorial debut - took an incredible 11 years to make. It is a powerful and deeply moving film that examines the impact of false reporting and follows a brother’s determined effort to reclaim his sister’s life from her infamous death.

The Witness starts with Bill’s investigation into what the witnesses actually saw. James Solomon is by Bill’s side as he pieces together the untold story. We hear from several people who lived in Kew Gardens at the time. Their (sometimes brutal) recollections feel all the more shocking because we are there with Bill as he discovers the details of that terrible night.

Interview by interview, the “facts” upon which Gansberg’s article was based begin to crumble. While Bill is incredibly sanguine, I felt outrage. The New York Times (and, later, other media organisations) did not let the facts stand in the way of a good story - and a family suffered for over 40 years as a result.

Gansberg was asked to write the story by A. M. Rosenthal. Rosenthal was the paper’s Metropolitan Editor in 1964 and a powerful figure in the media world (he became executive editor of The New York Times between 1977-1988).

Rosenthal went on to write a book about Kitty’s murder called Thirty Eight Witnesses. Despite the revelations of false reporting and accusations of flawed journalism, he is unrepentant. More than that, in a conversation with Bill he seems unconcerned about how the report affected Kitty’s family.

Watching him talk to Bill - who is the epitome of grace and respect throughout - is absolutely enraging. He is dismissive and he is arrogant. Rosenthal knew that the published story was untrue and, to serve his own agenda, he kept it alive anyway.

In 2016, David Dunlap wrote another article about Kitty for The New York Times. This time, thankfully, he concludes that the problem with Gansberg’s article “was that some key facts were wrong.”

Solomon’s film reveals the danger of fake news - on an intimate level (the impact on Bill’s life alone is devastating) and also on a universal level. “This account, published by The New York Times on March 27, 1964, all but guaranteed that the name Kitty Genovese would live on in infamy and that her family and friends would spend the next fifty years having their grief compounded by a terrible lie,” the director says.

The investigation into Kitty’s murder brings some comfort to the Genovese family. However, for Bill it is not enough (in the film he acknowledges his obsession). He investigates his sister’s killer - Winston Moseley - and, in a tense and moving meeting, talks to Moseley’s son, the Reverend Steven Moseley.

Bill is desperate to reclaim Kitty - to show the world that she was more than just a victim. As a result, having exposed the inaccuracies behind the reporting of her death, The Witness goes on to bring Kitty back to life via the memories of her family, friends and, in heartbreaking animated scenes, her girlfriend Mary Ann Zielonko.

It really is remarkable how The Witness conveys Kitty’s vibrant character. Suddenly thanks to these fond recollections, photos and snippets of archive footage, there she is - a person and no longer just a metaphor for society’s ills.

The Witness is an incredible, powerful and emotional documentary - I was gripped throughout and deeply moved by Bill’s journey in honour of his sister. Solomon concludes that Bill’s “determination to see this through, and his unending devotion to Kitty, transformed what was a cautionary tale of man’s inhumanity to his fellow man into an affirmation of our shared humanity.”

Bill goes to some brave and extreme lengths to uncover answers (including hiring an actress to recreate the attack in truly chilling scenes). It would take a hard heart not to feel invested in his story and want Bill and all those who loved Kitty to find peace.